By: Erika Schmitt

When asked in a 2002 Time interview about Princess Leia’s hair inspiration, George Lucas responded: “In the 1977 film, I was working very hard to create something different that wasn't fashion, so I went with a kind of Southwestern Pancho Villa woman revolutionary look, which is what that is. The buns are basically from turn-of-the-century Mexico. Then it took such hits and became such a thing. In the new trilogy, the same thing applies, to try and do something timeless. I'm just basically having a good time” (Cagle, 2002).

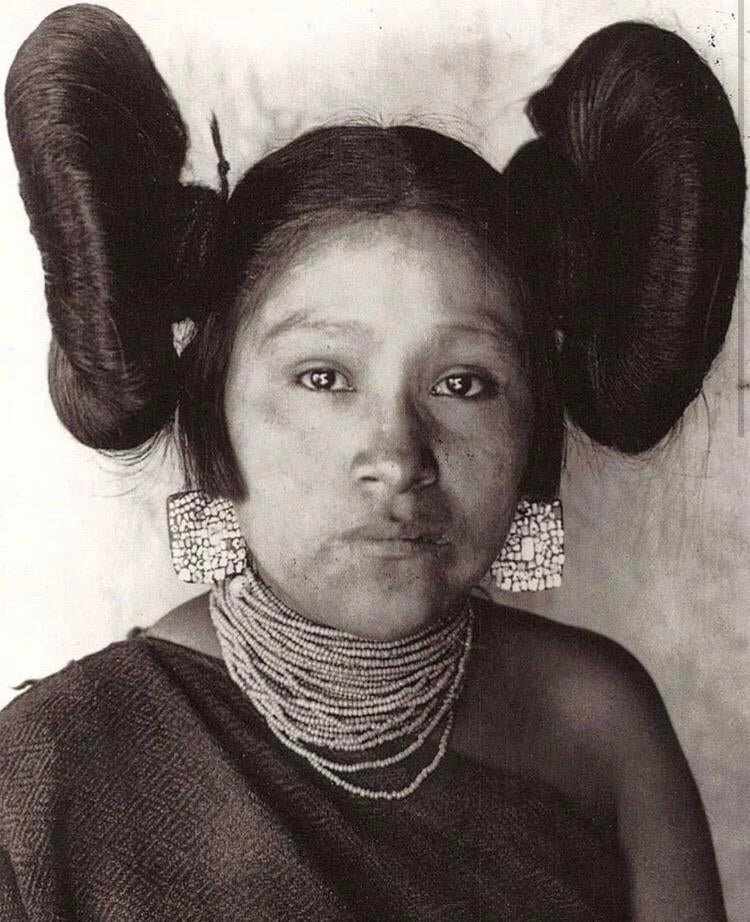

Although there has been some discrepancy about the accuracy of this claim since the practicality of such a hair-style would impede day-to-day chores for soldaderas (Drury, 2016). Some scholars suggest that the hairstyle was actually inspired by hairstyles worn by the Hopi tribe in Arizona (Drury, 2016). To coincide with the soldadera reputation as a fighter, during a 1977 interview Carrie Fisher explains, “ George… didn’t want a damsel in distress. [He] didn’t want your stereotypical princess… a sort of victim, frightened, incapable of dealing with the situation without ‘the guy.’ He wanted a fighter; he wanted someone who was independent” (Drury, 2016). Although the Hopi tribe’s hair is reminiscent of Princess Leia - and by extension her mother, Padme Amidala - Lucas and Fisher have personally attested to these remarkable women inspiring the look and demeanor of our beloved Princess/General. So who were these soldaderas and how did they inspire Lucas to create such an iconic character?

Hopi maiden wearing traditional squash blossom or butterfly whorl hairstyle

Photo courtesy of Native-languages.org

Senator Padma Amidala from Episode II - Attack of the Clones

Photo courtesy of Minq.com

The Mexican Revolution

The Mexican revolution, which lasted almost a decade (1911-1920), was a period of political instability due to a series of uprisings sparked by the fall of Porfirio Diaz. After seizing power in 1876, Porfirio Diaz would govern Mexico for the next 31 years. Diaz’s presidency was known for being corrupt and violent while helping the upper class and favoring foreign interests instead of domestic ones (Fernandez, 2009). During an interview in 1910, Diaz stated that he would not be running for another term, which sparked a political frenzy that Diaz had not anticipated - it is speculated that Diaz intended to run again all along, and only made the false announcement as a political stunt. As such, an upper-class land owner by the name of Francisco Madero challenged Diaz for the presidency. Unfortunately, Madero would be jailed and lose the election but in the following year of 1911, many Mexicans who had supported Madero rose up and revolted against the Porfiriato (Fernandez, 2009). Although Madero would eventually become president, he proved to be a weak leader who under delivered on his promises regarding land reform. His successor, General Victoriano Huerta, would murder Madero in his first week of office. Huerta’s dictatorship did not last long either and was overthrown by Venustianio Carranza in 1914. With the creation of the Constitution of Mexico in 1917, some scholars mark this as the end to the revolution while others declare the end of the revolution with the presidency of Alvero Obregon - who also led a coup that resulted in the murder of Carranza (History Detectives). Mind you, this is an incredibly watered down version of events meant to provide a backdrop to our leading ladies.

Soldaderas

Under the leadership of Diaz, women were considered second-class citizens. In the Constitution of 1857, women were not even considered citizens and because of this were extremely dependent upon the males in their family and in the Civil Code of 1884, a married woman could not enter into a contract, sell property, or oversee the education of her children - although she was allowed to teach only her own children thanks to a communal code. This patriarchal society favored men in a way that limited women in nearly every aspect of their lives. Women were responsible for the family while upholding expectations dictated by the Catholic Church (Fernandez, 2009). Prior to the 1911 revolution, women had no chance of being equal to men; the Mexican Revolution changed that.

There were many different reasons that women decided to join the revolution and become soldaderas. The word itself, soldadera, has a questionable direct translation, which seems fitting, considering there was no one role that a woman could perform as a soldadera. Two of the main roles for soldaderas were the camp follower or the soldier. The camp follower took on many tasks and was, essentially, the backbone of the army due to the lack of infrastructure and camp logistics, especially with the revolutionary forces (El Informador, 2010). As her main duty, the camp follower cared for the men by cooking, cleaning, maintaining weapons, transporting gear, setting up camp, foraging, providing medical care, smuggling all while caring for her own children and/or while pregnant - anything that was needed, she would dutifully supply (Fernandez, 2009). However, not all women were willing participants. If a woman chose to not follow her father, husband, or other familial male, that left her vulnerable to kidnapping from other factions who entered the male-less towns and forced women into servitude or else die. As the revolution continued and news of kidnappings spread, more women chose to follow men into battle (“Soldaderas”).

Two defiant soldaderas, ready for combat

Photo courtesy of JSTOR.org

By contrast, the soldaderas who chose to fight were usually in the lower ranks of the armies, sometimes choosing to adopt a male alter-ego in order to join. Changing one’s name to the masculine form, binding one’s chest, speaking lower, and dressing masculine were all ways that women skillfully hid their identities in order to support a cause they believed in. For those that succeeded, a majority of them were probably a part of the lower-class because one of the main reasons for the revolution was land reform and the lower-class’s lives depended upon farming (“Soldaderas”). For the soldaderas who did not need to care for a man, they possessed considerable freedom that they did not have previously. These women were able to challenge societal norms by taking on sexual partners, they had no intention of marrying, and they demonstrated that they were not docile but a person who wore bandoliers and wielded guns - a very radical idea at the time. By proving they were willing to die on the battlefield for what they believed in, soldaderas earned respect and equality (ish) from their male counterparts (Fernandez, 2009). Colonel Petra “Pedro” Herrar was known for her fearlessness in battle and should have been credited for the siege of the town Torreon. Colonel Maria Quinteras de Meras was a gifted soldier who outranked her husband (“Soldaderas”). Colonel Clara de la Rocha was a guerrillacommander who played an important role in seizing the city of Culiacan (Garcia, 2016). These women were but a small portion of those who took it upon themselves to challenge the status quo.

Colonel Clara de la Rocha, with her father General Herculano de la Rocha. This photo was on display with the traveling exhibit “Rebel, Jedi, Princess, Queen: Star Wars™ and the Power of Costume”

Photo courtesy of Snopes.com

Princess/General Leia Organa Photo courtesy of Allure.com

Although the soldaderas were national heroines, popular culture has shifted this reality to one that diminishes the accomplishments of these women in favor of focusing on their beauty and loyalty, renaming them “La Adelita” or “La Valentina” due to popular folk songs (Fernandez, 2009). Thankfully, the Chicana Feminist Movement has reclaimed the soldaderas to accurately represent these historical figures (“Soldaderas”). Princess Leia underwent a similar transformation when the infamous “Slave Leia” title, more known for her metal bikini than anything else, was rechristened “Huttslayer” by Claudia Gray in 2016’s Star Wars: Bloodline, focusing on her heroism rather than looks. Some of Leia’s most iconic photographs illustrate a woman, ready for action, with a blaster in her hand, just like the weapon toting soldaderas. General Leia was able to demonstrate that she was capable and achieved the highest military rank while also being a woman. The Mexican Revolution would never have gone the way it did without the daring and heroism of the soldaderas, much like the Death Star rescue would never have succeeded if without Leia’s quick thinking. “Saving our skins,” indeed.

Sources

Cagle, Cassie, (2002). “So, What’s the Deal with Leia’s Hair?” Time. Accessed 17 November 2020. http://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,232499,00.html

Drury, Flora, (2016). “The Story Behind Leia’s Hairstyle.” BBC. Accessed 17 November 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38452953

El Informador, (2010). “Las “adelitas,” las otras revolucionarias” Informador. Accessed 17 November 2020. https://www.informador.mx/Suplementos/Las-adelitas-las-otras-revolucionarias-20101119-0203.html

Fernandez, Delia, (2009). “From Soldadera to Adelita: The Depiction of Women in the Mexican Revolution.” McNairs Scholars Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 1, Article 6. Accessed 17 November 2020.

https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1217&context=mcnair

Gacia, Arturo, (2016). “The Origins of Princess Leia’s Hairstyle.” Snopes. Accessed 17 November 2020. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/origins-princess-leias-hairstyle/

History Detectives. “Mexican Revolution.” PBS. Accessed 17 November 2020.

https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/mexican-revolution/#:~:text=In%20the%20pursuit%20of%2 0civil,long%20into%20the%20following%20decade

“Soldaderas.” Wikipedia. Accessed 17 November 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soldaderas